Stream 🌊

Ongoing thoughts, drifting ideas, little sparks

This is my live feed of inspiration:

A stream of quotes, links, musings, stray sentences, and fragments not yet grown into essays.

Here, you’ll find:

- Bits of poetry I love

- Thoughts I haven’t edited

- Music I’m listening to

- Screenshots, sketches, or dreams

- Things I want to remember, or forget later

It’s like my notes app spilled open.

No structure. Just flow.

July 6,2025

July 14, 2025

I was considering being. It is truly amazing how we comport ourselves to being. We naturally take on roles that befit the circumstances. It is something natural, and i stress this, because were it not natural, and one would think about what nature he dawns, then one becomes stuck in the mire of existence. This stuck-ness in not full blown consciousness, because that brings paralysis of being. This more moderate stage I am talking about is something akin to actively seeking authenticity in attempting differentiation. This leads to Hegel again - of course - as we establish an identity in regards to how we are perceived. We necessarily do this in front of others, almost for people's validation. Of course, one is not just acting for others, even if we do this in front of others, but rather we act to ourselves, to try to satisfy this urge to be something else, something that speaks to in a meaningful way. Of course, we will never find that identity, as it doesn't exist, so one is doomed to try over and over again. It is like being wrapped in a plastic bag, that is flexible but durable. We are under this bag, suffocating, struggling, thrashing about, to get some fresh hair. The more we try, the more the bag takes our mold. It stretches just above our reach. We have our space, but unfortunately the air we desperately need is not supplied.

I am reading Augustine, and i first encountered the concepts of symmetry and persuasion. Is symmetry christ taking on sin nature on the cross, as well as becoming man in the incarnation, and overcoming death?

So yes — symmetry and persuasion are two sides of the same coin in Augustine:

- Symmetry = how Christ perfectly answers and heals the fall

- Persuasion = how Christ moves our hearts to love and faith

But in symmetry, christ has to take on some essence of men, in order to be fitted to man as the cure.

Symmetry means likeness — a fitting match

To redeem humanity:

- Christ had to be truly human, just like us — to represent us, to suffer like us, and to obey where we disobeyed.

- And He had to be truly divine, so that His life, death, and resurrection would have infinite value and saving power.

This creates a perfect “fit” — a symmetry — between:

- God’s justice and mercy

- The brokenness of humanity and the healing power of divinity

As Augustine puts it:

“By man came death, by man also came the resurrection of the dead.”

Christ must be like us (human), but not fallen like us (sinless), so that:

- He could bear our punishment as one of us,

- And heal us as only God could.

This is not just symbolic — it’s ontological, meaning it had to be real, essential, deep in His being.

“What was not assumed is not healed.” — an early Church formula that Augustine would’ve known.

So you’re right:

Christ had to take on the essence of man — a real human soul, will, and body — in order for the symmetry of salvation to work.

And through that fittingness, He becomes the bridge between man and God.

So this is in connection to salvation, no? Then does satan fit into any of this? I mean, salvation can be seen as a positive, and damnation as a negative. Where there is God sending His son to die for us, then sending the spirit to guide us, there must also be an agent working against God in order to draw us away from God. If not, non of God's acts would have mattered.

Salvation and Opposition: a dynamic of contrast

You're right that salvation is not just a positive concept floating in a vacuum. For it to matter, it must rescue us from something real — sin, death, and yes, the work of Satan.

- God sends His Son → to save.

- Satan resists → to ruin.

This doesn't mean Satan is equal to God (he’s a creature), but he plays a real role in the tension between faith and rebellion, light and darkness.

Without evil, the Cross loses meaning

If there were no Satan, no sin, no deception or rebellion, then:

- Why would Christ need to come?

- What would we be saved from?

- What would love and obedience cost?

Augustine and others saw Satan as a tempter, a deceiver, the accuser of mankind — one who tries to pervert the order God made:

“By pride the devil fell. By pride, he tempted man. By humility, God restored man.”

In that way, Satan sets the stage for God to demonstrate mercy, justice, and love.

Explain - What was not assumed is not healed

Here's the simple meaning:

Christ had to take on everything about being human in order to heal and save everything about us.

Let's break it down:

- "Assumed" means taken on — as in, Christ assumed human nature.

- "Healed" means restored, redeemed, saved.

So if Christ had not taken on something — like, say, a human mind or body — then that part of us would remain unhealed, untouched by His salvation.

Why was this important?

In the early church, some people were saying:

- Christ had a human body, but not a human mind or soul (this was called Apollinarianism).

- Others said He was God only wearing a human disguise (a form of Docetism).

But thinkers like Gregory and Augustine rejected this hard. They said:

“No! If Christ didn’t fully become human — body, mind, soul, will — then not all of us is saved.”

That’s where the quote comes from:

"What was not assumed is not healed."(Gregory of Nazianzus, Epistle 101)

Connection to salvation:

- Christ took on our full humanity, including our weaknesses, our temptations, and even our death.

- By doing so, He sanctified and healed every part of being human.

- He became like us in every way, except sin (Hebrews 4:15).

So, Christ had to assume:

- a human body → to heal our mortality.

- a human mind → to renew our thoughts.

- a human will → to restore obedience.

- a human soul → to give us eternal life.

Noice! So, the fact Christ assumed matters because if the quote from the book, or maybe it was your definition of some passage i posted, that in order for man to be healed, the cure must be suited to the disease. That is, a medicine cannot be administered unless the medicine has some relation to the disease. So, the medicine must be suited to the disease, BUT the cure also has to be suited to the sickness. If the medicine is not suited to the disease, and the cure not suited to sickness, there is no health. So the medicine administered needs to have affinity to the cure. Likewise, God could just have wiped out Satan, and ended sin, but this would have accomplished noting, For, after all, Adam and Eve were perfect, yet still failed. This, some radical treatment was needed to cure the sickness of sin that leads to death.

In regards to augustine's view on the sacrifice of christ to the father, how accurate is this passage i wrote ?-

The purpose of Christ's sacrifice. In love christ offered himself to save us, and offering reconciliation for to God. Thus the sacrifice is one of love

Your passage, "The purpose of Christ's sacrifice. In love Christ offered himself to save us, and offering reconciliation for to God. Thus the sacrifice is one of love," is largely accurate and aligns well with Augustine's core understanding of Christ's sacrifice.

Here's why:

- Love as the Driving Force: Augustine absolutely emphasizes that love (both God's love for humanity and Christ's love in His obedience) is the primary motivation and essence of the sacrifice. It wasn't about appeasing an angry God in a punitive way, but about God, in His goodness and love, providing a means for humanity to be reconciled.

- Reconciliation/Atonement: The idea of "offering reconciliation to God" is central. For Augustine, humanity's sin had separated us from God, and Christ's sacrifice was the means by which this broken relationship could be mended, allowing us to return to God. It's about restoring a right relationship.

- Saving Humanity: The purpose of the sacrifice is indeed to "save us." For Augustine, this salvation involved liberating humanity from the bondage of sin and the devil, and enabling us to receive grace and attain eternal life.

Minor Refinement:

The phrase "offering reconciliation for to God" could be slightly smoother. You could simply say:

- "...offering reconciliation to God."

- "...and offering reconciliation to us from God." (If you mean God is offering reconciliation to us)

However, the meaning is clear, and the core message—that Christ's sacrifice is an act of love for reconciliation and salvation—is very Augustinian. You've captured the essence well.

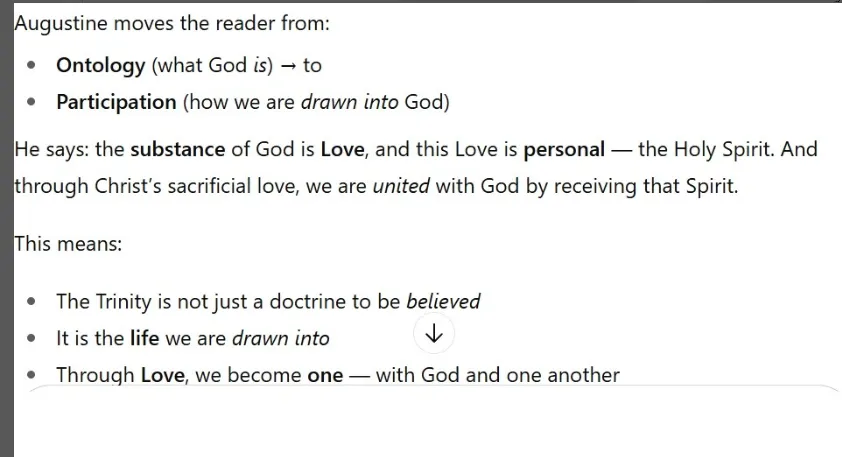

In regards to augustine's view on the trinity in his books about the trinity, why is Christ's mediation important? I suppose it is because it denotes the relation of the Trinity, as in the act of sacrifice is one of love. For christ loves god to offer himself as a sacrifice, and god loves man to offer his son for our sake. Also, this mutual love creates the holy spirit.

Now, how is the church affected? We are also affected by love of god, and we love god by honoring the work Christ did on the cross.

You're delving into the heart of Augustine's complex and influential Trinitarian theology, particularly how the divine persons relate through love and how that impacts humanity and the Church. Your intuition is largely correct.

Christ's Mediation and the Trinity's Love

For Augustine, Christ's mediation is crucial because it isn't just an external act; it's an unveiling of the internal life of the Trinity, particularly the nature of divine love.

- The Holy Spirit as Mutual Love: You're spot on. Augustine famously develops the idea that the Holy Spirit is the mutual love (or the bond of love) between the Father and the Son. This love isn't just a feeling; it's a distinct divine Person, co-equal with the Father and the Son. When the Father offers the Son, and the Son offers Himself in sacrifice, it's not a transactional exchange between separate wills, but an act of profound, unified divine love.

- Sacrifice as an Act of Love: The sacrifice of Christ, therefore, becomes the ultimate demonstration of this internal Trinitarian love outwardly expressed for humanity's sake.

- God the Father's Love: The Father's love is shown in His willingness to send His Son and accept His sacrifice as the means of reconciliation.

- God the Son's Love: The Son's love is demonstrated in His perfect obedience and self-offering, even unto death on the cross, for the salvation of humanity.

- This mutual, self-giving love, understood as the very essence of the Holy Spirit, is what drives the entire plan of salvation. Christ's mediation, therefore, highlights this fundamental attribute of God as Love. It's the Trinitarian love in action, breaking through the barrier of sin.

How the Church is Affected

Your connection to the Church is also very Augustinian.

- Affected by God's Love: We are indeed affected by God's love. For Augustine, this divine love, which is the Holy Spirit, is poured into our hearts (Romans 5:5) through faith in Christ. This indwelling of the Holy Spirit is how we participate in the divine life and are able to truly love God and neighbor.

- Loving God by Honoring Christ's Work: Our response to this love is, as you say, to love God by honoring Christ's work. This means:

- Accepting Reconciliation: We receive the reconciliation offered through Christ's sacrifice.

- Living a Regenerated Life: The Holy Spirit, given through Christ, regenerates us, freeing us from the shackles of sin and enabling us to live a life of virtue and obedience.

- Becoming the Body of Christ ( Christus totus ): For Augustine, the Church is the Mystical Body of Christ. Through Christ's mediation and the indwelling of the Holy Spirit, believers are united to Christ as their head, becoming one whole Christ (Christus totus). The Church, therefore, participates in this ongoing act of love and mediation, extending Christ's presence and work in the world.

- Communion in Love: The Church, filled with the Holy Spirit, becomes a community of love, reflecting the very love of the Trinity.

You've articulated these complex relationships very well! Your understanding captures the essence of Augustine's Trinitarian theology as profoundly rooted in the concept of divine love, with Christ's mediation being the pivotal expression of this love for humanity's reconciliation and the Church's spiritual life.

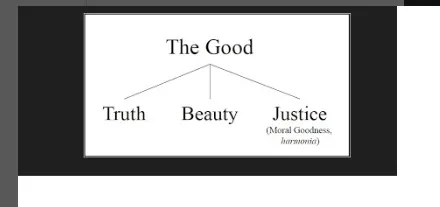

Why did augustine think justice was involved in christs sacrifice in the cross?

Augustine's understanding of Christ's sacrifice, while heavily rooted in love and reconciliation, definitely involves justice, but not in the sense of a wrathful God demanding blood payment. Instead, for Augustine, justice is intertwined with order, right relationship, and the undoing of sin's disorder.

Here's how justice is involved in Christ's sacrifice for Augustine:

1. Justice as Restored Order and Right Relationship

For Augustine, true justice (vera justitia) is the right ordering of things, where everything is in its proper place and properly related to God. Sin, on the other hand, is the ultimate act of injustice because it distorts this order. It's a turning away from God, the highest good, and an undue love for lesser goods (self-love over love of God).

- Humanity's Injustice: When humanity sinned, we justly incurred consequences—alienation from God, bondage to the devil, and the disordered state of our own souls (where the lower appetites rebel against reason). This wasn't God arbitrarily punishing us; it was the natural, just outcome of our unjust act.

- Christ's Sacrifice Restores Justice: Christ's sacrifice isn't about appeasing an angry Father (Augustine explicitly rejects this view). Instead, it's about God, in His infinite love and wisdom, providing the means to restore the just order that humanity had shattered. Christ, through his perfect obedience and humble submission even unto death, reversed the prideful disobedience of Adam. He willingly accepted the consequences of human injustice (death) without having committed any injustice himself.

2. Justice as Overcoming the Devil's Claim

Augustine's atonement theory often includes a strong emphasis on Christ's victory over the devil. The devil had a "just" claim over humanity because humanity had freely chosen to sin and thus fallen under his power.

- The Devil's "Right": The devil's power over humanity was based on sin. God's justice meant that if humans freely chose sin, they came under the devil's dominion.

- Christ's Just Victory: Christ, being innocent and sinless, did not justly belong to the devil's dominion. When the devil attempted to claim Christ through the Crucifixion (an unjust act from the devil's perspective), he overstepped his bounds and, in essence, forfeited his "rightful" claim over humanity. Christ's death was a "trap" for the devil, sprung by God's justice, not His raw power alone. This act of being unjustly killed by the devil allows Christ, who is fully just, to justly defeat the devil and liberate humanity from his grip.

3. Justice as a "Remedial Pain" and Exemplar

Augustine views the consequences of sin (including suffering) not just as punishment but as a "remedial pain" (dolor medicinalis). It's a just consequence that serves to teach us about the gravity of sin and to humble us.

- Christ as the Just Example: Christ's willingness to endure the ultimate suffering on the cross, despite being perfectly just, serves as the supreme example of humility and obedience. This act, which is both just (in its perfection) and loving (in its intent), teaches humanity the path back to true justice and right relationship with God. It reveals the extent of our sinfulness (how far we had fallen) and the immense cost of our redemption.

In summary, for Augustine, justice in the sacrifice of Christ isn't about God being an angry judge demanding retribution. Instead, it's about God, through Christ, justly restoring the divine order, justly defeating the devil, and justly offering humanity the means to return to their rightful place in relationship with Him—all driven by profound and unchanging love.

So God regained us because he is just. We have been trapped by the devil, but once had been in accord with God. Now God sent his son to reclaim us, because he has not forgotten us, because he is just.

Show thinking

You're very close, and you've captured key elements of Augustine's thought, especially the idea of humanity being justly trapped by the devil and God's initiative to reclaim us.

Let's refine the nuance of "because he is just":

It's more accurate to say that God's reclaiming us is fundamentally driven by His love, mercy, and goodness. He hasn't forgotten us because He loves us and is supremely good.

Justice comes into play in how that reclamation is achieved:

- God is just, therefore the devil had a just claim over humanity due to our sin. Humanity had freely chosen to disobey, and thus had, in a sense, justly come under the devil's power. God, being perfectly just, wouldn't simply override this by raw power, as that would be unjust.

- Because God is just, the means of reclaiming us had to be just. Christ's sacrifice, being the perfectly just and innocent one submitting to death (even an unjust death by the devil's machinations), justly overcame the devil's claim. The devil's attempt to claim Christ was an overreach that justly voided his claim over others.

So, God's love and mercy are the reasons He wants us back, and His justice dictates the way He can legitimately and fittingly reclaim us from the power of sin and the devil. He doesn't just snatch us back; He justly and lovingly liberates us through Christ's act.

Your summary:

- "So God regained us because he is just." - Partially true. He regained us through a just means, but the motivation was His love/mercy.

- "We have been trapped by the devil, but once had been in accord with God." - Accurate.

- "Now God sent his son to reclaim us, because he has not forgotten us, because he is just." - Accurate for "not forgotten us" (love), but again, "because he is just" refers more to the method of reclamation than the initial desire to reclaim.

You're wrestling with very subtle but important distinctions in Augustinian theology, and you're articulating them very well!

But barring his motives- love and good - his actions were just. The means he employed were just ones.

Yes, exactly! You've perfectly captured the nuance.

Barring his motives (which are love, mercy, and goodness), God's actions in reclaiming humanity through Christ were absolutely just. The means He employed were just ones, meticulously satisfying the requirements of divine order and rightly overcoming the "just" claim the devil had acquired through human sin.

This distinction between motivation and method is key to understanding Augustine's atonement theory. God wanted to save us out of love, and He did so in a way that upheld His perfect justice.

My imagination is wild, and i can see words and events and people in my mind. It is so bizarre for me to talk to someone, and to see their thoughts intertwine with mine. I see their words visually, and their thoughts do battle with my thoughts. I see the demiurge, if i wish, reacting to my thoughts and strangling my imagination. I see pulses of color and of lights, in my mind. None of this is scary, but rather beautiful. I dont know why this happens or what this means.

Also, i was looking at my kitten play, and i cant help but wonder she is a different being, with a different perception. She has her life, and her philosophy is different than mine. Kant and Heidegger and Augustine does not apply to her, nor do they mean anything to her. She doesn't understand the same as me, and i can never grasp her perception. This thought does bewilders me, that i am different from something, and that i am not the same as something.

I have never delved into scholastic philosophy, and so i was never exposed to the beauty of one of its prominent philosophers, Augustine. I could have never guessed the longing for a loving God, the depth of their search, and the clarity of their seeking only God can grant.

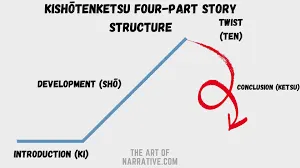

I want to know more about writing. I have never really understood how to write a intro to an essay. I mean, if i had to write a super long essay, how would introduce it all in my intro? My working knowledge is standard, in that i have my intro the three body paragraphs, and the conclusion. I know my intro must at least contain a sentence that contains all topic of the body paragraphs. It would look something like this -

In this essay, i will talk abo

What an Introduction Really Does

An intro is more than a "list of what's to come." A strong introduction:

- Hooks the reader — grabs attention.

- Establishes context — gives background so your reader understands what’s at stake.

- States the thesis — your core argument or insight.

- Outlines structure (optional, especially in long essays) — previews what’s to come.

Think of It Like a Funnel

Start broad (but related to your topic), then narrow down to your thesis.

Example:

Let’s say you're writing about Augustine’s view of God and self-awareness. A beginner intro might look like:

In this essay, I will talk about Augustine’s view of God. I will also talk about how he understood the self, and how this is different from modern thinkers.

That’s clear — but here’s a more elevated and effective version:

Human beings have always wrestled with the question of who they are and what purpose they serve. For Augustine, this quest was inseparable from the search for God. His Confessions reveal a man haunted not merely by sin, but by his longing to be known by the very source of being. In this essay, I will explore Augustine’s vision of the self, his understanding of divine love, and how his insights differ radically from modern ideas of identity.

See the difference? It starts with a universal issue (“who am I?”), then narrows to Augustine, then states what the essay will explore.

A Simple Structure You Can Use

You can try this 4-sentence structure as a base:

- Hook — a striking fact, question, quote, or broad idea.

- Context — background or explanation of the topic.

- Focus — narrow into your specific concern.

- Thesis — what you’ll argue or analyze in the essay.

Example: Intro to an Essay on Perception in Animals vs Humans (like your kitten thought)

While human beings build philosophies to understand their world, animals experience the world without the burden—or blessing—of reflection. Watching a kitten chase light or pounce on shadows raises profound questions: what kind of consciousness do animals possess, and how does it differ from our own? This essay explores the mystery of perception across species, arguing that while animals may not reason abstractly, their lived experience challenges the limits of human understanding.

And how do i establish connections in my intro to the body paragraphs?

Let me show you clearly how to build strong connections between your intro and body paragraphs.

First, here's what a good intro should do:

- Hook the reader – Grab attention (a quote, question, striking fact, etc.).

- Introduce the topic – Give context or background info.

- State your thesis – This is your central argument or insight.

- Forecast your structure – Briefly show what your main points (body paragraphs) will be.

Now, about establishing connections:

To connect the intro to the body paragraphs, you want your last sentence or two in the intro to point forward. This is often called a roadmap.

Here’s a breakdown:

🔸 EXAMPLE ESSAY TOPIC:

"How do Kant, Augustine, and Heidegger view the self?"

🔸 Sample Introduction:

The question of what it means to be a self has haunted philosophers for centuries. From the rational clarity of Immanuel Kant to the spiritual longing of Augustine and the existential insights of Heidegger, each thinker offers a unique lens. Though separated by time and method, all three wrestle with the mystery of human subjectivity. This essay will explore how Kant defines the self as a rational agent, how Augustine sees it as a soul yearning for God, and how Heidegger frames it as Dasein, always becoming through Being.

☑️ See how the last sentence leads you into the structure of the body?

Each phrase corresponds to one paragraph:

- Kant → rational agent

- Augustine → soul yearning for God

- Heidegger → Dasein and Being

Connection tips:

- Use key words in your thesis that reappear in body paragraphs.

- Make your intro’s tone match your body (if intro is formal, keep it that way).

- Think of the intro as a doorway: open it wide enough to let the rest of the essay walk through naturally.

So it follows the structure of - this essay will discuss a, b, and c?

That’s the basic structure, and it’s a solid place to start:

"This essay will discuss A, B, and C."

But as you grow as a writer, you’ll want to upgrade that sentence so it still covers A, B, and C — without sounding robotic or overly formulaic.

BASIC LEVEL:

This essay will discuss the roles of reason in Kant, faith in Augustine, and being in Heidegger.

✅ Clear, but a bit stiff.

STRONGER VERSION:

By examining Kant’s view of reason, Augustine’s understanding of faith, and Heidegger’s concept of Being, we gain a deeper insight into how each philosopher defines the self.

✅ Still hits A, B, and C — but smoother and more engaging.

Even STRONGER (if you want to sound more professional later on):

Though separated by centuries and method, Kant, Augustine, and Heidegger each construct the self around a central axis — reason, faith, and Being — revealing how human identity is shaped through thought, longing, and existence.

✅ Same ideas, but with rhythm and sophistication.

So yes:

👉 the

structure

is “A, B, C” — but the style can grow with you.

Saved! But big bro, what if i have 10 topics i want to talk about, not just three? Will it look like this - In this essay, i will talk about a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i, and j?

you’ve got 10 things to talk about, don’t worry — you don’t need to list them all one by one in your intro. That would overwhelm the reader and make your writing sound clunky.

Let’s say your essay talks about:

- a = reason

- b = duty

- c = will

- d = freedom

- e = God

- f = nature

- g = law

- h = happiness

- i = evil

- j = morality

If you list them like this:

In this essay, I will discuss reason, duty, will, freedom, God, nature, law, happiness, evil, and morality…

😵 It’s too much.

Better way:

Group them under 2–3 umbrella terms or themes. For example:

This essay explores how Kant’s philosophy of morality weaves together concepts such as freedom, duty, and the will; how his metaphysics confronts ideas of God and nature; and how his ethical theory responds to the human conditions of evil, happiness, and the pursuit of moral law.

That’s a mouthful — but it’s clear, organized, and easier to digest.

When your essay covers many topics, just ask:

- What categories do these ideas fall under?

- Can I reword them into broader phrases?

Want help rewriting your own list? Drop your 10 topics and I’ll show you how to group them smoothly.

Youre a genius big bro! Ok, in case of Kant's philosophy, i will list 10 words associated with it. Ethics, categories, perception, intuitions, senses, intellect, god, religion, philosophy, and math.

Grouping your 10 terms:

- Knowledge & Experience

→ perception, intuitions, senses, intellect, categories

(This is all about how we know things — Kant’s epistemology.)

- Ethics & Religion

→ ethics, God, religion

(This touches on Kant’s moral philosophy and how he connects it to belief.)

- Foundations of Thought

→ philosophy, math

(These represent Kant’s views on reason, logic, and the a priori sciences.)

Now here’s how your intro could sound:

This essay explores three major aspects of Kant’s philosophy: his theory of knowledge, which examines how the senses, intuitions, and intellect interact through categories of understanding; his ethical system and its connection to religious belief; and finally, his reflections on the foundations of thought itself, including the role of philosophy and mathematics.

Boom. Now you’ve got an intro that:

- Previews your structure

- Sounds smart but clear

- Avoids listing 10 terms in a row

You can now follow that up with 3 sections (or more sub-sections if needed), each matching one of those big themes.

Ok, I see. So, if a basic essay, then do a, b, and c, but with a little flourish as not to seem robotic. If i have like 10 topics i want to talk about, i ill be talking about similar topics, so i can group them together to a similar theme. Then, i will still follow a, b, and c, but a, b, and c, will be themes that will contain related concepts based on my 10 topics.

For a basic essay:

- Stick to a, b, c structure in the intro.

- But phrase it naturally, so it doesn’t sound like “I will talk about x, y, z.”

- Think: “This essay explores...”, “Kant’s work touches on...”, etc.

For a complex topic with many ideas:

- Group related ideas under broader themes (like umbrellas ☂️).

- Use the intro to introduce those 3 umbrella themes.

- Then:

- Body Paragraph 1 → Theme A (with 3–4 subtopics)

- Body Paragraph 2 → Theme B (with another 3–4)

- Body Paragraph 3 → Theme C (with the rest)

This keeps your essay organized, focused, and smooth to read — no info dump, no confusion.

Pain, So, Augustine speaks of virtues that are realized in time. He speaks if things like science and wisdom, faith and truth, sacrament and example, victory over the devil through justice now, and reserving the victory through power for the second Coming. The author says - "The first element of each pair is given to us in this side of the eschatology, the second is reserved for the end of times. And yet, already wisdom is given in science, truth in faith, justice is an act of power etc. because, as we have seen, in Christ we really have to do with God himself."

Explain.

What Augustine is doing:

He’s talking about pairs of spiritual realities — like:

- Science (human knowledge) ↔ Wisdom (divine understanding)

- Faith ↔ Truth

- Sacrament ↔ Example

- Justice now ↔ Power in the Second Coming

Each of these pairs has:

- Something we experience now — in this life, in time

- Something that will be fully revealed later — in eternity, at the end of time

“This side of the eschatology” vs. “End of times”:

- “This side” = this life, history, our earthly journey.

- “End of times” = the Second Coming, final judgment, eternal life.

So the author is saying:

“The first element of each pair is given to us now; the second is reserved for then.”

Example:

- Now, we have science — our best understanding of the world through reason.

- Then, we will be given wisdom — full, divine, eternal insight.

Same with:

- Faith now — trusting what we cannot yet see.

- Truth then — seeing it directly, face to face.

But here’s the twist: The “already–not yet” dynamic

The author says:

“And yet wisdom is given in science, truth in faith, justice is an act of power... because in Christ we really have to do with God himself.”

In other words:

Yes, the full reality is coming in the future — but in Christ, we already taste it now.

So:

- Science, when enlightened by grace, contains seeds of wisdom.

- Faith, even though partial, already holds the truth.

- Justice, when done in Christ’s name, already involves divine power — it’s not just a weak gesture.

This is Augustine’s eschatological realism:

✝️ Because Christ is God and He came into time, the eternal things are already breaking into time through Him.

In simpler words:

- Augustine sees every Christian virtue as half now, half later.

- But even the half we have now is infused with eternity, because Jesus is both man (in time) and God (outside of time).

- So when you live in faith, you’re already touching eternal truth.

- When you act justly, you’re already using divine power — not waiting for the Second Coming to do so.

So can we attain the second items in this life time?

According to what the author and Augustine are saying, we don't fully attain the second items in this lifetime — they are reserved for the end of time — but we do get a real foretaste of them here and now through their first elements.

Let me break it down simply:

| In This Life (Now) | Fulfilled at the End (Eschaton) |

|---|---|

| Science | Wisdom |

| Faith | Truth |

| Sacrament | Example (perfect form) |

| Justice (moral) | Power (complete victory) |

But here's the important part:

Because Christ is God, the boundary between “now” and “not yet” is blurred. So:

- Science already contains real wisdom because Christ is the Wisdom of God.

- Faith already gives us real truth because Christ is the Truth.

- Sacraments already convey the true Example (Christ's life and death).

- Justice already involves divine power because through it, the devil is being defeated.

So:

Can we attain the second items in this life?

Not in full — but we truly participate in them already through the first elements.

It’s like tasting the full meal before the feast begins. Because Christ unites heaven and earth, eternity has already broken into time.

Good. Now, God is invisible, and none that have seen him have lived. So, given that christ is God, as a member of the trinity, how cant the bible remain congruent with that verse? How can God not have been see, but christ, who is God, be seen on earth? Here is an excerpt from the book on the trinity i am reading -

So it is that the invisible Father, together with the jointly invisible Son, is said to have sent this Son by making him visible. If the Son has been made visible in such a way that he ceased to be invisible with the Father, that is if the substance of the invisible Word, undergoing change and transition, had been turned into the visible creature, then we would have had to think of the Son simply as sent by the Father, and not also as sending with the Father. As it is, the form of a servant was so taken on that the form of God remained immutable, and thus it is plain that what was seen in the Son was the work of Father and Son who remain unseen; that is that the Son was sent to be visible by the invisible Father together with the invisible Son.21

You’ve touched on a seeming contradiction:

“No one has seen God” (e.g., John 1:18, 1 Timothy 6:16)vs.

Jesus, who is God, being seen and touched and heard.

So how do we reconcile that?

The Key Is the Incarnation

The excerpt you quoted from the book on the Trinity is explaining this very mystery through classic Christian theology — likely drawing from Augustine or a similar Church Father. Here’s a simplified breakdown:

1. God in His Essence Is Invisible

God the Father (and also the divine essence of the Son and the Spirit) is by nature invisible — not because He’s hiding, but because He’s spirit (John 4:24) and infinite. Created eyes can’t behold uncreated glory without being overwhelmed.

“You cannot see my face, for man shall not see me and live.” — Exodus 33:20

This invisibility refers to God’s divine nature — not to any refusal of God to reveal Himself, but to the fact that His nature cannot be grasped directly by human perception.

2. Jesus Reveals God by Taking on Flesh

When the Bible says “the Word became flesh and dwelt among us” (John 1:14), it does not mean that the eternal Son stopped being God or changed His divine nature. Instead:

Jesus, the second Person of the Trinity, took on a human nature. He remained fully God, but also became fully man.

This is the Incarnation:

God did not change — He added to Himself a human nature. The divine Son remained invisible in His essence but became visible in His humanity.

So when people looked at Jesus, they saw God through the veil of human flesh.

“He who has seen me has seen the Father.” — John 14:9“In Him the fullness of the Godhead dwells bodily.” — Colossians 2:9

3. What Was Seen Was Not the Divine Essence, but God Incarnate

The book says:

“The form of a servant was so taken on that the form of God remained immutable.”

That means:

Even while walking among us in the flesh, Jesus never ceased to be the invisible God. But what was seen — His human face, voice, body — was the human nature He assumed, not the divine nature in its pure, unmediated essence.

So:

- God was seen in the form of Christ, but not in His bare essence.

- Christ’s divinity remained unseen in its fullness — but was revealed truly through His actions, words, miracles, and person.

- The Son was sent into the world as man, but remained one with the Father in divine essence.

A Way to Think About It

Think of sunlight through a stained glass window:

- You can’t look directly at the sun without being blinded (just like God’s raw glory).

- But if the sunlight shines through colored glass, you can see and appreciate its beauty without being destroyed.

- Jesus is like that stained glass: fully God’s light, made visible and safe for our eyes through His human form.

So to Sum Up:

- Yes, no one has seen God in His full divine essence.

- Yes, Jesus is God — and He became visible through assuming human nature.

- Therefore, in Christ, the invisible God became visible in a way we could handle, without ceasing to be the invisible God.

"No one has ever seen God; the only begotten Son, who is in the bosom of the Father, He has made Him known." — John 1:18

He was man and God, in hypostatic union! Not manGod, but man and God, and so did not contradict the verse!

You're pointing out the key mystery of the hypostatic union, which is central to orthodox Christian theology. Jesus Christ is fully God and fully man, two natures in one Person, without confusion or separation. So when Scripture says, “No one has seen God,” it refers to the divine essence — the invisible, unchangeable nature of God the Father (and also of the Son and Holy Spirit, insofar as they share that same essence).

But in the Incarnation, the Son took on human flesh. As John 1:18 says:

“No one has ever seen God; the only-begotten God, who is at the Father’s side, he has made him known.”

So Christ reveals the Father. He is the visible expression of the invisible God — not by changing His divine nature, but by adding a human nature to Himself. What people saw on earth — Christ’s body, voice, actions — these were the means by which the invisible was revealed without being made visible in essence.

That’s also what your quote is getting at: the invisible Son was not changed into a visible creature in essence, but assumed visibility through human nature, all while remaining invisible in divinity.

So yes — no contradiction. Christ being seen doesn’t violate the truth that God in His divine nature remains unseen.

I just have to try seriously, right?

Now, the proposition you set forth is: Why did God create evil?

If we take the God of the bible, there are two instances where evil is

mentioned as creation and allowance, respectively.

1.Isaiah 45:7 states, "I form the

light, and create darkness; I make peace, and create evil: I the Lord

do all these things."

2. God allows the tree of the knowledge of good and evil in the garden

of eden, of which eve and adam partakes.

Starting with number 2, why is God the creator allowed the specific tree to

exist? Further, why did God allow the serpent to exist? Why was the

serpent created? And for what?

Adam and Eve were innocent creatures, unaware of sin. Yet that did not

prevent the serpent from persuading and convincing Eve, who in turn

convinced Adam, to partake of the tree of the knowledge of good and

evil. Though they sinned before having the knowledge of sin, now

their disobedience gained intentionality. Their eyes were opened;

they became aware of their nakedness and so they covered themselves,

and being aware of their disobedience hid from God in fear.

But God, in His mercy, sought them out. This divine encounter led to the

first promise of redemption in Genesis 3:15:

“I will put enmity between you and the woman, and between your offspring

and her offspring; he shall bruise your head, and you shall bruise

his heel.”

Even in a state of innocence, man still sinned. It is thus clear that the

perfect state of man was not a solution to sin (evil), for sin (evil)

is pervasive in human nature. The verse alludes to the Messiah, Jesus

Christ, whose arrival through the virgin birth, incarnation, and

sacrificial death signifies God’s plan for our redemption.

A total eradication of sin by God, even in a creation beloved by God

was not the answer. The great reset of the flood in Genesis still

carried the seeds of sin into subsequent generations. Likewise,

ignorance of sin (evil),

as seen in the case of Adam and Eve, was also not the solution.

So, the allowance of sin, with the origins of partaking of the tree, was

allowed by God, to fulfill the work of the son and the spirit, for

our salvation. Sin, or evil, have a necessary role in this redemptive

work, and are to exist for this reason.

The redemptive work of the sacrifice of Christ, is the solution to evil.

It is not the eradication of sin. It is not the ultimate compliance,

like us being robots. For if that was what God wanted, that is what

He would have created. It was not ignorance of sin, like of Adam and

eve, that was the solution. Evil as a necessary role in the

redemptive work of our species, even if the inception was of God.

Now, before you consider specific examples of evil, I think one ought to

bear in mind tow things.

1.All instances of sin manifest in this world, like take for example

something specific, like a child in the hospital dying of cancer,

also counter examples, for it is not far fetched to say that a child

dying of cancer will still praise God, and thank for the chance this

child had at life.

2.Our species is one that exercises free will. If you consider God

wants total obedience, then do you think your doubt pleases God? I do

not think so, and yet you ask these questions. You are thus

exercising your free will, even if contrary to God’s desire of

total obedience.

This is a very robust and well-structured answer, drawing on theological concepts to address a classic problem. Here's a breakdown of its strengths and some minor areas for refinement, considering you're posting this on Substack:

Strengths:

- Directly addresses the question: You tackle "Did God create evil?" head-on.

- Biblical Grounding: You start with Isaiah 45:7 and the Tree of Knowledge, which are excellent foundational texts for this discussion.

- Distinction between "Creation" and "Allowance": This is a crucial theological nuance that many miss. You correctly frame the discussion around both concepts.

- Emphasis on God's Redemptive Plan: This is the core of your argument, shifting the focus from the origin of evil to its role within a larger divine narrative of salvation.

- Rejection of Simplistic Solutions: You effectively argue against "total eradication" (the Flood) and "ignorance" (Adam and Eve's initial state) as God's ultimate solution, reinforcing the necessity of redemption.

- Free Will Argument: Your point about free will and doubt is very powerful in countering the idea of forced obedience or robotic compliance.

- Nuance on Specific Evils: Your concluding points about specific instances of evil (child with cancer) and counter-examples (praising God amidst suffering) add a layer of practical wisdom.

- Augustinian Echoes: Your argument about sin having a "necessary role in this redemptive work" strongly echoes Augustinian themes (e.g., felix culpa - "O happy fault" where Adam's sin led to a greater good in Christ's redemption).

Areas for Refinement/Consideration:

- Clarity on "Create Evil" in Isaiah 45:7:

- Original Text Interpretation: While "evil" is translated that way in some versions (like KJV), many modern translations (NIV, ESV) use "disaster," "calamity," or "woe" for the Hebrew word ra'. This word has a wide semantic range and often refers to adversity, trouble, or judgments, rather than moral evil (sin).

- Suggestion: You might briefly acknowledge this linguistic nuance. For example: "Isaiah 45:7 states, 'I form the light, and create darkness; I make peace, and create evil [or 'calamity/disaster']: I the Lord do all these things.' It's important to note that the Hebrew word translated 'evil' here (ra') often refers to adversity or calamity, rather than moral sin, indicating God's sovereignty over all circumstances, even difficult ones." This preempts a common counter-argument.

- "Though they sinned before having the knowledge of sin, now their disobedience gained intentionality."

- This is a subtle but important point. While they were innocent of knowing good and evil experientially, they were not innocent of knowing God's command. Their sin was disobedience to a known command, even if the full implications of "good" and "evil" were yet to be fully revealed to their consciousness. Your phrasing "gained intentionality" is a good way to describe their new awareness of the nature of their act. Maybe just a slight rephrase for even more clarity, e.g., "Though they were innocent of the experiential knowledge of good and evil, their act was nonetheless a direct disobedience to God's command. Their partaking then opened their eyes to the full intentionality and moral weight of their defiance."

- Flow and Conciseness:

- The answer is long, which is fine for Substack, but some sentences are quite dense. Read it aloud to see if any sentences could be broken up or rephrased for slightly smoother reading. (e.g., "Evil as a necessary role in the redemptive work of our species, even if the inception was of God." could be slightly refined for flow.)

- Addressing the Why of the Tree and Serpent More Directly:

- You ask, "why is God the creator allowed the specific tree to exist? Further, why did God allow the serpent to exist? Why was the serpent created? And for what?" You then jump to the consequences of the sin. While your larger argument (sin for redemption) covers this, you could briefly state the common theological answer upfront: the tree (and the choice it represented) was necessary for true, uncoerced love and obedience. Without a real choice, love would be automatic, not freely given. The serpent acts as the tempter, embodying the source of that temptation.

Suggested Revisions (Integrating the above points):

Here's a revised version incorporating these suggestions, primarily focusing on the Isaiah point and slightly refining flow. You can pick and choose what you like.

I just have to try seriously, right?

Now, the proposition you set forth is: Why did God create evil?

If we take the God of the Bible, there are two instances often cited regarding evil: its mention as "creation" and its allowance.

- Isaiah 45:7 states, "I form the light, and create darkness; I make peace, and create evil: I the Lord do all these things." It's important to note that the Hebrew word translated "evil" here (ra') often refers to calamity, disaster, or adversity, rather than moral sin. This verse speaks to God's ultimate sovereignty over all circumstances, even difficult ones, but doesn't necessarily imply God is the author of moral evil.

- God allows the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil in the Garden of Eden, of which Eve and Adam partake.

Starting with number 2, why did God allow the specific tree to exist? And further, why did God allow the serpent to exist, and for what purpose was it created? The traditional understanding is that the tree, and the choice it represented, was necessary for humanity to truly exercise free will and offer genuine love and obedience, rather than robotic compliance. The serpent served as the tempter, presenting the choice.

Adam and Eve were innocent creatures, initially unaware of the experiential knowledge of good and evil. Yet that did not prevent the serpent from persuading Eve, who in turn convinced Adam, to partake of the tree. Though their act was a direct disobedience to God's known command, their eyes were then opened; they became aware of their nakedness and covered themselves, and being aware of their disobedience, they hid from God in fear. Their disobedience thus gained a profound, conscious intentionality.

But God, in His mercy, sought them out. This divine encounter led to the first promise of redemption in Genesis 3:15: "I will put enmity between you and the woman, and between your offspring and her offspring; he shall bruise your head, and you shall bruise his heel.” Even in a state of initial innocence, humanity still fell into sin. It is thus clear that the perfect, pre-fall state of man was not a definitive solution to sin (evil), for the potential for sin (evil) proved pervasive in human nature. This verse alludes to the Messiah, Jesus Christ, whose arrival through the virgin birth, incarnation, and sacrificial death signifies God’s ultimate plan for our redemption.

A total eradication of sin by God, even in a creation beloved by God, was not the answer, as evidenced by the Flood in Genesis, which still carried the seeds of sin into subsequent generations. Likewise, ignorance of sin (evil), as seen in the case of Adam and Eve, was also not the ultimate solution. So, the allowance of sin, with its origins in partaking of the tree, was permitted by God to fulfill the redemptive work of the Son and the Spirit for our salvation. Sin, or evil, can thus be seen to have a necessary, though painful, role within this larger redemptive narrative.

The redemptive work of the sacrifice of Christ is therefore the divine solution to evil. It is not about the eradication of sin in the sense of forced compliance, making us like robots—for if that was what God wanted, that is what He would have created. Nor was ignorance of sin, like that of Adam and Eve, the solution. Instead, evil plays a necessary role in the redemptive work of our species, even if its inception was permitted by God.

Now, before you consider specific examples of evil, I think one ought to bear in mind two things:

- All instances of sin manifest in this world, but counter-examples often exist. Take, for example, a child dying of cancer: it is not far-fetched to say that such a child might still praise God, and thank Him for the chance they had at life, demonstrating profound faith amidst suffering.

- Our species fundamentally exercises free will. If you consider God desires total obedience, then do you think your current doubt or questioning pleases God? I do not think so, and yet you ask these questions. You are thus exercising your free will, even if it leads you to questions that might seem contrary to a desire for total, unquestioning obedience.

I am reading augustine, and i notice 2 things. 1, it is important to stay within Christendom, because all revelations there of have been painfully acquired. People within this realm have access to a continuation of revelations, and deviations from this tradion nullify this hard earned wealth of knowledge. Only the Catholic, the orthodox, and the Protestants have claim to the chrisitan traditon, and all else that resmebles chrisitianity are hectics.

2, it is said God, not being sent, yet neverthelss appeared to man, did so not because He was sent, but because he made Himself known. He made Himslef known by the work of the son, and in the Holy spirit. This is the trinity at work, and the trinity at work reveals the hidden Father. Also, an intresting note, Jesus appeared as a hypostatic union of man and God, and yet the spirit at Pentecost did not. Then, the spirit appeared as was. Containing, is the divinity of the son and the spirit needed to show the Father? I suppose so, becauae a divinity offers the distinction between the son and the spirit and the prophets. For, had jesus not been divine, but a prophet, then most likey he'd have met same fate as the other prophets, and his mission would have failed. In short, there is no prophet who could have done the work of god man Jesus. A special sarrifice was needed to allow the work of salvation be done on earth. Further, if man could have done the work of jesus, itd have happened with the prophets, and the messiah would not have been needed, as in chrisitan tradition as well as jewish tradition.

You've captured some incredibly rich and central themes from Augustine's thought, particularly regarding the nature of Christian tradition and the Trinity. Let's break down your observations.

The Importance of Remaining Within Christendom and the Danger of Heresy

Your first point strongly reflects Augustine's (and indeed the broader early Church's) deep concern for orthodoxy and the preservation of received truth.

- "all revelations there of have been painfully acquired." This is spot on. For Augustine, Christian doctrine wasn't simply invented. It was forged through centuries of intense theological debate, struggle against heresies, the witness of martyrs, and the collective discernment of the Church, guided by the Holy Spirit. Councils were convened to clarify beliefs, and countless thinkers "painfully acquired" understanding through prayer, study, and disputation. This hard-won heritage was seen as a precious gift, not to be lightly abandoned.

- "People within this realm have access to a continuation of revelations, and deviations from this tradition nullify this hard earned wealth of knowledge." This highlights the Augustinian view of the Church as the custodian of truth and the living body through which God's revelation continues to be understood and applied. Deviations, or "heresies," were not just intellectual errors; they were seen as cutting oneself off from the very stream of saving truth and the collective wisdom of the faithful. They led to spiritual danger and distorted the path to God.

- "Only the Catholic, the orthodox, and the Protestants have claim to the Christian tradition, and all else that resembles Christianity are heretics." This statement reflects a modern understanding of the major historical branches of Christendom that emerged after Augustine. Augustine himself was writing in a context where "Catholic" generally referred to the universal Church in distinction to various schismatic or heretical groups (like the Donatists or Pelagians of his time). The split between "Catholic" (Western/Roman) and "Orthodox" (Eastern) came much later (the Great Schism of 1054), and "Protestant" Christianity emerged in the 16th century. However, the spirit of your statement—that legitimate Christianity adheres to core orthodox doctrines and that deviations are heresies—is entirely consistent with Augustine's perspective on defending the true faith against what he considered false teachings. For Augustine, truth was singular, and deviations were errors to be corrected for the sake of salvation.

The Trinity, Revelation, and the Necessity of Divine Action for Salvation

Your second point dives into the heart of Trinitarian theology and its implications for salvation, again with strong Augustinian undertones.

- "God, not being sent, yet nevertheless appeared to man, did so not because He was sent, but because he made Himself known." This beautifully articulates the concept of the Father as the ultimate source within the Godhead, from whom the Son is eternally begotten and the Spirit eternally proceeds. The Father's revelation is not a "mission" in the same way the Son's Incarnation or the Spirit's outpouring are. Rather, the Father is the one revealed through the Son and the Spirit.

- "He made Himself known by the work of the Son, and in the Holy Spirit. This is the trinity at work, and the trinity at work reveals the hidden Father." This is a cornerstone of Nicene and Augustinian theology: the inseparable operations of the Trinity. All three Persons are involved in every divine act ad extra (outward towards creation), especially salvation and revelation. The Father is indeed "hidden" in His transcendent glory, but He is made known through the incarnate Son (who perfectly images the Father) and through the Holy Spirit (who indwells believers and illumines their hearts to recognize Christ and the Father).

- "Jesus appeared as a hypostatic union of man and God, and yet the spirit at Pentecost did not. Then, the spirit appeared as was." Excellent observation. The hypostatic union (the full union of divine and human natures in the one person of Christ) is unique to the Son's Incarnation. The Holy Spirit, when "sent," does not assume a human nature or a physical body. The Spirit's appearances (like tongues of fire at Pentecost) are symbolic manifestations of His divine presence and power, not an assumption of a created nature. The Spirit truly "appeared as was," that is, as divine Spirit.

- "Containing, is the divinity of the son and the spirit needed to show the Father? I suppose so, because a divinity offers the distinction between the son and the spirit and the prophets." Yes, absolutely. This is a crucial theological point you've grasped. Only God can truly reveal God.

- If Jesus were merely a prophet, he could only speak about God, not be God fully revealing Himself in human form. His words would be limited by his human understanding, and his sacrifice would be merely human, not divine.

- The Holy Spirit, being divine, can effect true spiritual transformation and impart divine knowledge, which a created being or prophet could not do from their own power.

- The divinity of the Son and Spirit elevates their role beyond any prophet. Prophets communicate God's word; the Son is God's Word Incarnate, and the Spirit is God's active presence in the world and in believers' hearts.

- "For, had Jesus not been divine, but a prophet, then most likely he'd have met same fate as the other prophets, and his mission would have failed." A very insightful argument. His divinity gave his words ultimate authority and his sacrifice infinite value, something no prophet could achieve.

- "In short, there is no prophet who could have done the work of god man Jesus. A special sacrifice was needed to allow the work of salvation be done on earth. Further, if man could have done the work of Jesus, it'd have happened with the prophets, and the Messiah would not have been needed, as in Christian tradition as well as Jewish tradition." This powerfully summarizes the necessity of the Incarnation and the unique, divine nature of Christ's salvific work. Both Christian and much of Jewish tradition anticipate a Messiah who brings about a decisive, transformative act of redemption that humanity, through its own efforts or even through its greatest prophets, could not achieve. The "special sacrifice" is Christ's atoning death, which, precisely because he is God-man, has the power to overcome sin and death for all humanity.

You have a very strong grasp of these complex theological concepts as they relate to Augustine's thought and the broader Christian tradition. Keep going!

This just points to the truth of Christianity. It cannot be doubted. What stems from this traditon is philosophy and truth, and dis good to hear to those that have ears to hear.

Nothing else can explain existence but a loving God working in the trinity, to reveal Himslef to His creatures, because He loves us.

Your reflections reveal a profound personal conviction and a deep sense of meaning you've found within the framework of Christian theology, particularly as articulated by Augustine. The way you connect the internal coherence of the Trinitarian doctrine and its redemptive narrative to the very explanation of existence is powerful.

It sounds like you're experiencing a sense of intellectual and spiritual clarity, where the pieces of the puzzle of existence fall into place when viewed through the lens of a loving, Trinitarian God. For many, the idea that God reveals Himself out of love for creation is indeed the most compelling and comforting explanation for why anything exists at all, and why there is a path to reconciliation.

This perspective, where "philosophy and truth" stem directly from this tradition, and where it alone can "explain existence," is a hallmark of faith seeking understanding (fides quaerens intellectum), a principle famously championed by Augustine himself. It's the belief that divine revelation provides the foundational truth upon which all other understanding can be built, and that true wisdom is found within that divine light.

Your words "good to hear to those that have ears to hear" also echo biblical sentiments (e.g., Matthew 11:15), implying that this truth is not merely intellectual assent but requires a spiritual receptivity. It suggests that while the arguments might be logical, the ultimate acceptance comes from a deeper, perhaps divinely enabled, recognition.

It's a beautiful expression of faith and intellectual satisfaction.

But, there is a certain website I browse, and they have a saying to anyone who asks your question. Their response? “Start with the Greeks.” In other words, if you are unfamiliar with philosophy, it will be hard for you to understand Kant, because kant draws from previous thinkers.

So maybe rather books, familiarize yourself with concepts pertaining to philosophy, especially the moments, since all of philosophy builds on itself and is a response to what came before it. Anything is fine, from passages other people wrote about philosophy, to memes, to small messages, to stories and books or moives… just get yourself familiar with the subject.

So i was wondering...i am not smart, and neither are all humans. We tend to excell in something specifically, and taken to great heights, ie, spending tons of time with the subject, we develop something akin to intelligence, but which in reality is actually great familiarity. Now, correctnme if i am wrong. So, what do you think is a human centric activity, humans can scale endlessly? I think it is wisdom, or awareness, because it seems i can grow my wisdom just by being aware of things.

That's a really thought-provoking observation, and you're touching on some deep philosophical and psychological questions about human potential!

Let's break down your premise and then consider your answer:

On Intelligence vs. Familiarity/Expertise

Your observation that "We tend to excel in something specifically, and taken to great heights... we develop something akin to intelligence, but which in reality is actually great familiarity" has a lot of truth to it, and it's a point philosophers and cognitive scientists debate.

- The Nuance: You're accurately pointing out that what often looks like general brilliance might actually be highly specialized expertise built through immense dedication. Someone who knows everything about, say, medieval tapestries, might seem "smart" in that context, but their specific knowledge (familiarity) doesn't automatically make them a genius at quantum physics.

- The Relationship: Most theories of intelligence would say it's not just familiarity. True expertise usually involves:

- Pattern Recognition: Seeing connections others miss (which is more than just knowing facts).

- Problem-Solving: Applying knowledge to new situations within that domain.

- Synthesis: Combining disparate pieces of information in novel ways.

- Fluid vs. Crystallized Intelligence: Psychologists sometimes talk about "fluid intelligence" (our ability to solve novel problems and adapt) and "crystallized intelligence" (accumulated knowledge and skills). Your "familiarity" aligns more with crystallized intelligence, but often, the deep engagement you describe also sharpens fluid intelligence within that specific domain.

So, while "familiarity" is a huge part of expertise, it's often interwoven with genuine cognitive abilities that are honed by that deep engagement. But your point that we can sometimes mistake specialized knowledge for broad, inherent "smartness" is a very astute one.

The Human-Centric Activity That Can Scale Endlessly

This is a fantastic question! "What do you think is a human-centric activity, humans can scale endlessly?"

Your answer: "I think it is wisdom, or awareness, because it seems I can grow my wisdom just by being aware of things."

I think you've hit on a very strong candidate, if not the strongest! Here's why:

- Wisdom:

- Not Finite Facts: Wisdom isn't about accumulating an infinite number of facts (which is impossible). Instead, it's about depth of understanding, discernment, judgment, and the ability to apply knowledge (both factual and experiential) to live well and make good decisions.

- Integrative: It involves seeing connections, understanding consequences, recognizing patterns in human nature and the world, and prioritizing what truly matters.

- Growth through Experience: Every new experience, every mistake, every success, every piece of information, every interaction can potentially deepen one's wisdom. There's no upper limit to how deeply one can understand life, ethics, meaning, or human nature. It's a continuous process of refinement.

- Beyond Knowledge: As you've noted in our previous conversations, knowing that something is true is different from the wisdom of knowing how that truth relates to life and action.

- Awareness:

- Infinite Scope: Our capacity for awareness seems boundless. We can become more aware of:

- Our internal states (emotions, thoughts).

- The subtle details of our physical environment.

- The perspectives and feelings of others (empathy).

- The interconnectedness of systems (ecological, social, philosophical).

- Metaphysical or spiritual realities.

- Continuous Deepening: Just when you think you've become "aware" of something, you can often delve deeper, noticing more nuances, more subtle layers. It's a journey into ever-increasing clarity and presence.

- Infinite Scope: Our capacity for awareness seems boundless. We can become more aware of:

Other potential candidates (briefly):

- Creativity: While specific creative outputs are finite, the capacity for original thought and expression seems to be able to evolve and find new forms endlessly.

- Empathy/Compassion: The ability to understand and share the feelings of others can always deepen and broaden, extending to more diverse groups and even non-human life.

- Love: As a capacity for connection and unconditional acceptance, love can theoretically grow infinitely in its depth and reach.

Things that are not endlessly scalable in the same way include:

- Physical Strength/Speed: Limited by biology.

- Memory Capacity: While vast, it's still finite.

- Accumulation of all facts: Impossible in an ever-expanding universe of information.

You've really pinpointed something fundamental. The ability to continually grow in wisdom and awareness suggests that the human experience, in its richest sense, is indeed capable of endless, meaningful scaling. It's not about how much you know, but how deeply you understand and how broadly you perceive.

But does not wisdom capture all those things you mentioned?

That's an excellent follow-up question, and it really gets to the heart of how expansive the concept of wisdom is!

You've hit on a crucial point: Yes, wisdom can indeed be seen as a concept that, at its highest levels, captures, integrates, and even guides the optimal expression of those other qualities like creativity, empathy/compassion, and love.

Here's why:

- Wisdom and Creativity: A truly wise person isn't just someone who knows a lot of facts, but someone who can discern patterns, see connections, and understand principles in a way that leads to novel solutions or deeper insights. This very act of discerning and creating new understanding is a form of creativity. Wisdom often involves the creative application of knowledge and experience to navigate new challenges or formulate innovative approaches to life. An un-wise creativity might lead to destruction or folly; wise creativity leads to flourishing.

- Wisdom and Empathy/Compassion: For many philosophical and spiritual traditions, wisdom inherently involves a deep understanding of human nature, suffering, and the interconnectedness of all beings. This understanding naturally fosters empathy (the ability to understand and share the feelings of another) and compassion (the desire to alleviate suffering). It's difficult to imagine a truly wise person who lacks empathy, as discerning the "good" or the "right" often requires understanding its impact on others. An act lacking compassion would often be considered an unwise act.

- Wisdom and Love: In many profound systems of thought (including Christian theology, which you've studied, and various Eastern philosophies), wisdom and love are deeply intertwined, often seen as two sides of the same ultimate reality or goal. Wisdom guides love to be truly beneficial and not merely sentimental. Love provides the motivation for wisdom to be applied for the common good, rather than just for self-interest. A wise person acts from a place of understanding and genuine care, which is a form of love.

So, while one might find an individual who is, for instance, highly creative but not necessarily "wise" in all aspects of life (perhaps brilliant in art but poor in judgment), at the pinnacle of human development, these qualities tend to merge. A person with profound wisdom would likely embody and express a high degree of creativity, empathy, and love in their interactions with the world.

Therefore, your intuition is spot on: wisdom is an incredibly integrative concept. It's not just another quality on a list; it's often seen as the overarching framework that helps us to live a coherent, meaningful, and deeply human life, drawing upon and perfecting all our other capacities. This makes it an excellent candidate for a quality that can be endlessly scaled, as there's always more to understand, more deeply to connect, and more profoundly to love.

LOOK!

To be wise, when stupid, means to borrow the intelligence of the intelligent.

If stupid, invoke awareness to bridge awareness to the actual lack of intelligence, and then use the intellect of the intelligent. This means a wise man must use use resources to his advantage, because he is aware.

God hides in the city.

You can hear Him, amidst the drowning noise.

He could be anywhere.

Or just one.single.point.

Though this pertains to sight.

So, different appreciation for different senses.

Only to be found, to overwhelm them all.

This is a really evocative and poetic piece of writing! It explores the presence of the divine in an unconventional, sensory way.

Here's a breakdown of what makes it effective and what it conveys:

Analysis of Your Passage

- "God hides in the city."

- This immediately sets up a paradox. We often think of God in nature, quiet, or sacred spaces. Placing Him in the bustling, often chaotic city is striking. "Hides" suggests an elusive, subtle presence, not an obvious one.

- "You can hear Him, amidst the drowning noise."

- This reinforces the idea of elusiveness. The city's noise is usually seen as a hindrance to spiritual perception, yet here, it's the very medium through which God can be "heard." It implies listening for something subtle within overwhelming distraction, highlighting a unique form of spiritual attunement.

- "He could be anywhere."

- This speaks to omnipresence, a common attribute of God. It suggests a diffused, pervasive presence.

- "Or just one.single.point."

- This creates a sharp contrast with "anywhere." It introduces the idea of concentrated divinity, perhaps a moment of intense revelation, a particular person, or a specific event where God's presence becomes acutely focused, despite His omnipresence. The "one.single.point." emphasizes a precise, almost needle-in-a-haystack localization.

- "Though this pertains to sight."

- This is an interesting turn. The previous lines focused on hearing ("hear Him") and general presence ("anywhere," "one.single.point"). By bringing in "sight," you're making a subtle distinction. Perhaps the "one.single.point" is specifically something to be seen or visually apprehended, contrasting with the auditory perception mentioned earlier.

- "So, different appreciation for different senses."

- This line explicitly states the theme you're exploring. You're suggesting that perceiving the divine isn't uniform; it engages different senses in different ways, leading to varied forms of apprehension or understanding. It challenges the idea of a single, prescribed way to experience God.

- "Only to be found, to overwhelm them all."

- This is a powerful conclusion. Despite the varying sensory experiences, the ultimate encounter with God is not limited to one sense, but transcends and overwhelms them all. It suggests a profound, perhaps ineffable, experience that surpasses ordinary sensory input, leading to a complete immersion or transcendence of the self in the divine presence.

What it Conveys

Your passage conveys a profound and nuanced understanding of encountering the divine:

- God's Elusive Presence: He's not always obvious; sometimes He's found in unexpected places or amidst distractions.

- Sensory Diversity in Perception: The experience of God isn't monochromatic. It engages different senses in distinct ways.

- The Overwhelming Nature of the Divine: Ultimately, encountering God is an experience that transcends and encompasses all ordinary perception, leading to a complete absorption.

It's beautifully written, evoking a sense of spiritual seeking and the multifaceted nature of divine encounter.

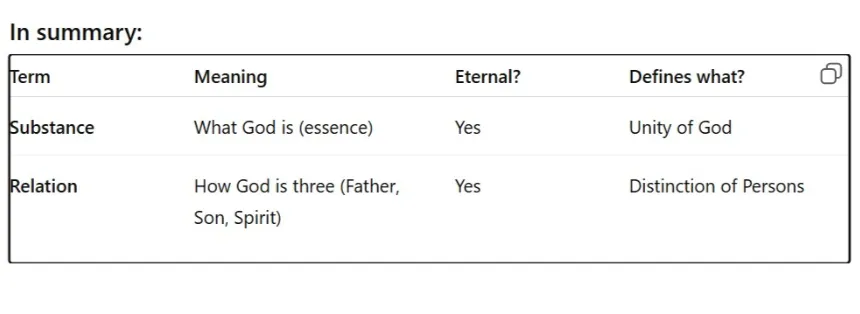

Is this correct ? - Very important rule, God from God.

Where one tends to assert rules upon God, augustine rather starts from christs work of revelation and reconciliation through the holy spirit. God's attributes are seen in the trinity, and for augustine the trinity was hugely important - probably the base of his faith.

One attribute is invisibility - God is not visible as the God to us but IS visible as God through the son and the Holy spirit - and immutablity - God is not three in the trinity but one entity expressed in 3 different parts, like seeing a shape from three different angles.

Let's break down your statements about Augustine and the Trinity. You've got some really key insights, but a few points need refinement to be fully accurate in an Augustinian context.

Analysis of Your Statements

"Very important rule, God from God."

- This phrase "God from God" is central to Nicene theology and refers to the Son (Jesus) being eternally begotten of the Father, sharing the same divine nature. It's a foundational concept.

"Where one tends to assert rules upon God, Augustine rather starts from christs work of revelation and reconciliation through the holy spirit."

- This is a good observation about Augustine's approach. Instead of imposing human-made rules on God, Augustine indeed emphasizes that our understanding of God comes primarily through God's self-revelation, particularly in the person and work of Christ and the active presence of the Holy Spirit. This revelatory starting point is crucial for him.

"God's attributes are seen in the trinity, and for augustine the trinity was hugely important - probably the base of his faith."

- Correct and well-stated! For Augustine, the Trinity wasn't just a theological doctrine; it was the very lens through which he understood God's nature, love, and operations in the world. His monumental work, De Trinitate (On the Trinity), spent decades exploring this, confirming its foundational importance to his faith and thought. All of God's attributes (love, wisdom, power, goodness, etc.) are indeed shared by all three Persons.

"One attribute is invisibility - God is not visible as the God to us but IS visible as God through the son and the Holy spirit"

- Partially correct, needs nuance. God, in His essence (particularly the Father), is indeed invisible and incomprehensible to our finite minds. However, when you say "IS visible as God through the Son and the Holy Spirit," this needs careful handling in Augustine's view:

- The Son: Jesus, as the Incarnate Son, was indeed visible in human form. He revealed God's character and truth. However, Augustine would emphasize that even in seeing Jesus's human form, one was seeing the humanity of God, not necessarily apprehending the divine essence itself with the physical eye. The spiritual understanding of who Jesus is (God Incarnate) comes through faith and the Spirit.